Luci Gutiérrez, from the linked article.

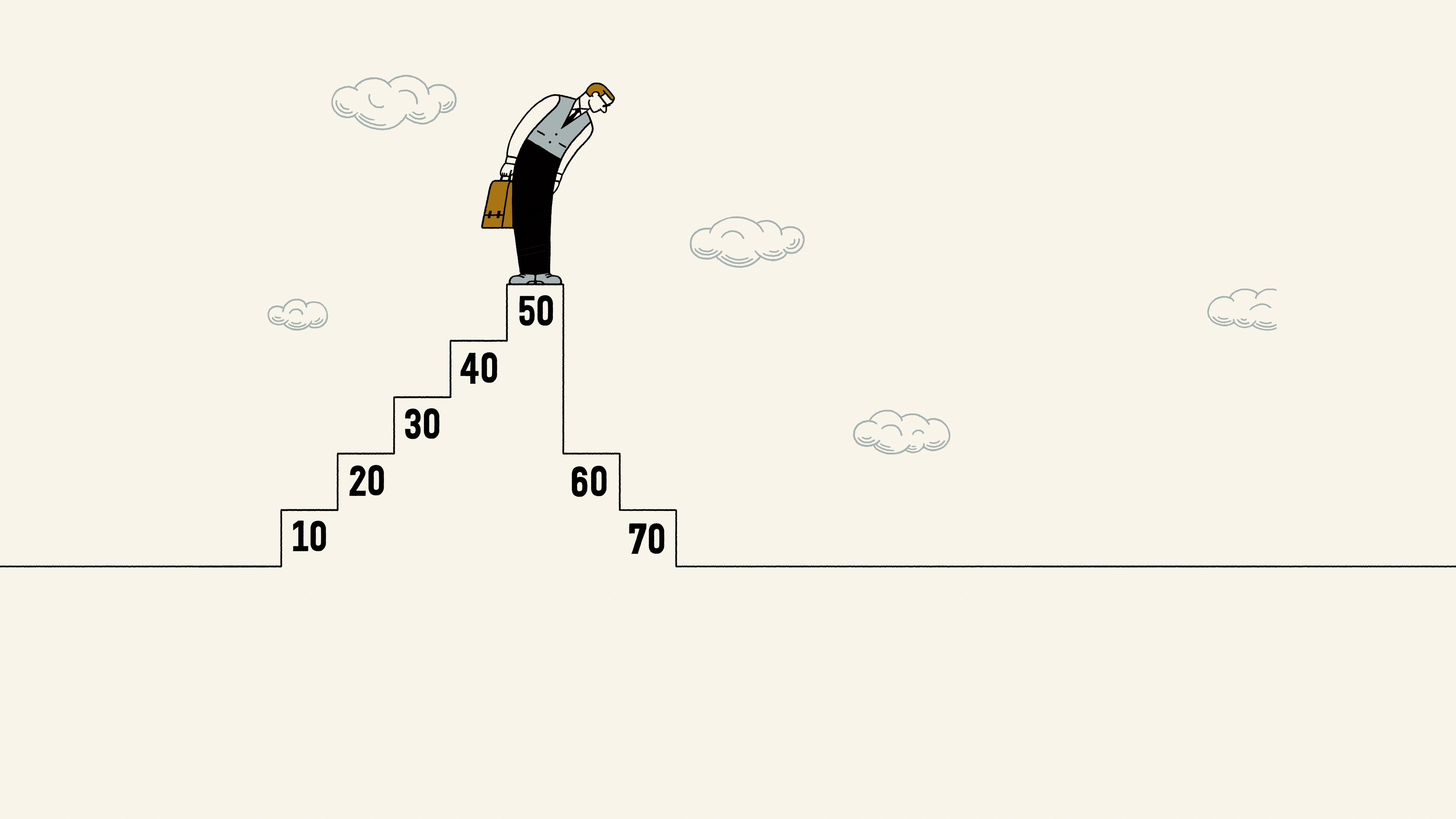

Arthur C. Brooks, in his July 2019 Atlantic article Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think, confronts an uncomfortable truth: professional decline begins much earlier than most people expect.

The core of Brooks’ argument is based on psychologist Raymond Cattell’s work from the 1940s, which distinguished between fluid and crystallized intelligence.

Fluid intelligence—analytical capacity, processing speed, and the ability to solve novel problems—peaks in one’s early thirties and then declines precipitously, which explains why many tech entrepreneurs achieve fame and fortune in their twenties but enter creative decline by age 30.

Crystallized intelligence, conversely, represents the ability to use knowledge accumulated over time—the essence of wisdom. This form of intelligence tends to increase through one’s forties and doesn’t diminish until very late in life. Careers that depend primarily on fluid intelligence tend to reach their peak early, while those utilizing more crystallized intelligence tend to reach their peak later.

Brooks suggests that as we age, we should embrace this change and prepare in advance for a transition, planning to move from innovator to mentoring and teaching roles.

Another study that struck me is the 2007 study by UCLA and Princeton researchers, also mentioned in the article, that showed that elderly people who rarely or never felt “useful” were nearly three times more likely to develop depression than those who frequently felt useful. It may seem like common sense, and it probably is, but we should keep this in mind when interacting with our elderly loved ones.

I’m turning 55 this year. I’m still grinding like there’s no tomorrow, though. I am in a peculiar position, as running my own company and being responsible for the people working with me makes transitioning to something else a less-than-easy option. Additionally, in my field, continuous learning is essential, as failure to do so can render one obsolete in short order; therefore, I am committed to and used to ongoing training. I’m not slowing down, at least not yet. Experience makes decision-making easier (and wiser?), and learning still comes naturally, perhaps because of the knowledge base I can draw upon.

That’s how I feel today as I ponder Brooks’ article, but I’ll admit that the thought of slowing down surfaces sometimes. Also, I’m often the only grey-bearded individual in the crowd (especially noticeable at conferences where I’m speaking), and that must mean something.