The other day we did a .NET 7 Spotlight event at this month’s DevRomagna meetup. The speakers were Ugo Lattanzi and me. In my session, I chose to talk about my top 7 new features in .NET 7 (pun intended.) What follows is a mix of my preparation notes and what I ended up really saying1.

1. Performance

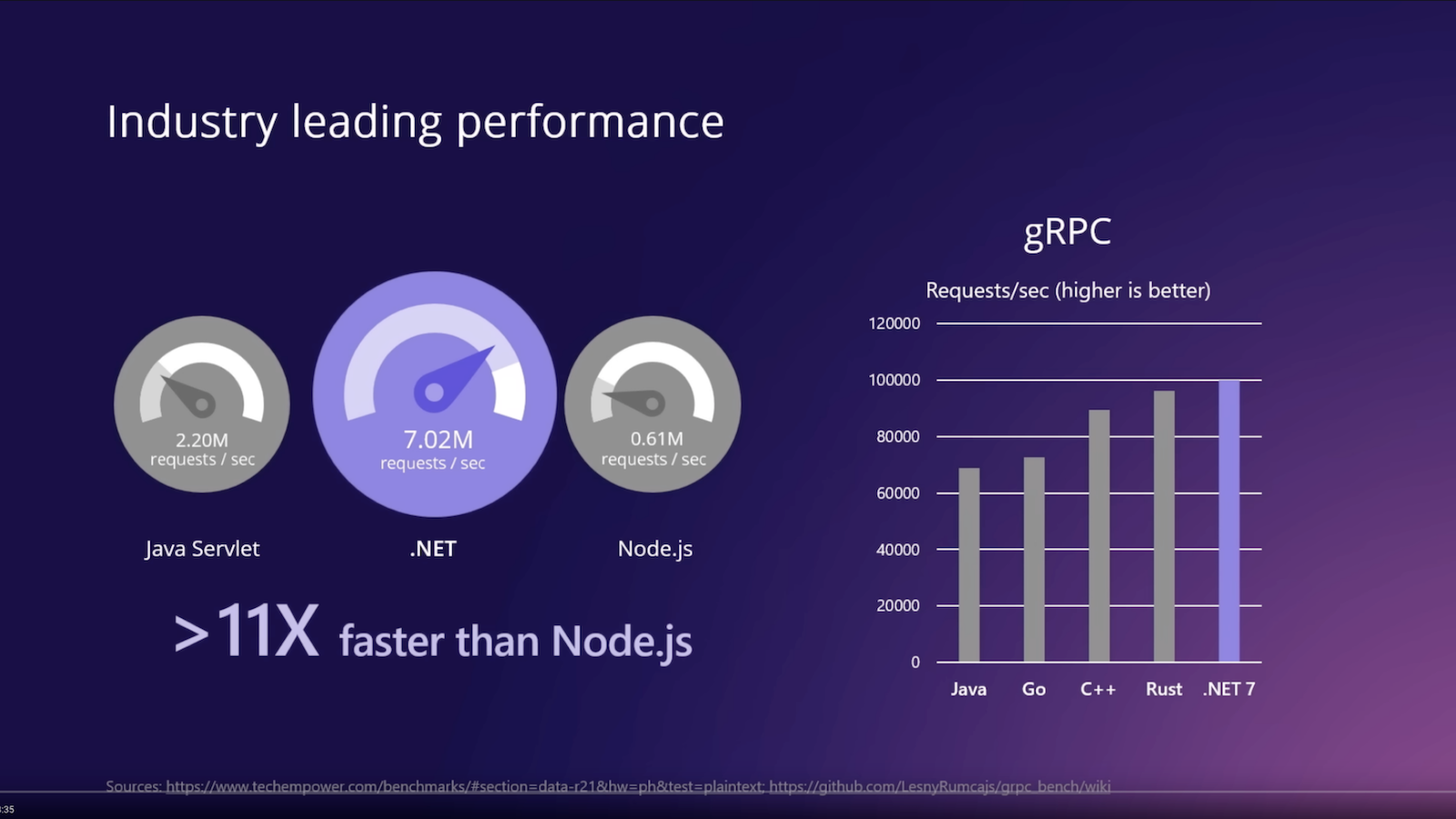

Since the initial release of “new dotnet” (.NET Core), performance has always been a critical goal for the .NET team. Starting with .NET 5, performance gains have been skyrocketing. .NET 6 was a lot faster than 5, and now, well, I’m surprised by the remarkable performance improvements in .NET 7. Stephen Toub posted a remarkably long (255 printed pages!) in-depth analysis of the performance improvements in .NET 7. one That was followed by articles dedicated to ASP.NET Core 7 and MAUI 7 performance gains. At .NETConf 2022, a particular slide caught everyone’s attention.

I recall seeing the same slide at the .NET 5 release, so this one is must be updated version. I’m more impressed with the gRPC graph than the big “11x faster than Node” one. Being faster than Node doesn’t break the news these days, but being quicker than Go, C++ and Rust? That’s one bold statement you have right there.

An exciting article surfaced a while ago on this specific topic. In it, Dustin Moris Gorski presents an in-depth analysis of the ASP.NET Core 7 code used for the TechEmpower Framework Benchmark referenced in the above slide. The results are… fascinating. That code is undoubtedly not what mere mortals tend to run in their production systems. It is super-performance-optimized, often ditching canonical, built-in, and wildly adopted features in favor of low-level, high-performance and precisely hand-crafted alternatives. Dustin’s article is a masterpiece for several reasons; I suggest you invest your time reading it.

But yeah, despite this glitch, the takeaway is that .NET 7 is speedy, faster than previous versions, and on par with, if not (far?) superior to, most stacks and frameworks. The Stephen Toub’s article is a testament to the massive work done and the achievements obtained.

Most importantely, we get most of these speed benefits for free, just by

upgrading to .NET 7. And the good new is, the upgrade is as easy as changing

the framework moniker from, say, net6.0 to net7.0 and upgrading the

Microsoft dependencies to v7.0.0.

2. C# 11 required modifier

As a consequence of the C# release cycle alignment to that of.NET itself (which

is much faster), recent versions of C# see fewer features announcements than in

the past. A good thing in my opinion. Of the several appreciable new features

coming with C# 11, a remarkable one is the required modifier.

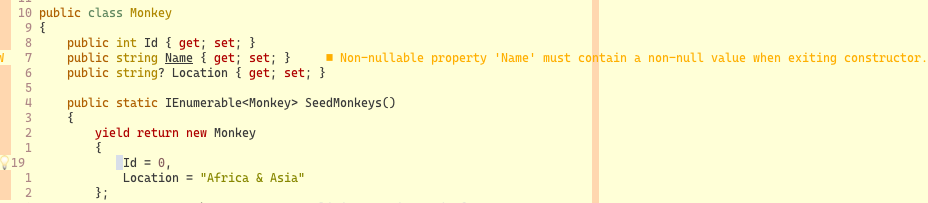

When you enable nullable checks in a project, non-nullable string properties are flagged with warning that they should be initialized with a non-null value when exiting the constructor:

A common workaround has been these properties them with a null! value. That

is like telling the compiler that we know they should be initialized with a

non-nullable, but well, let’s initialize them with a null value first, just in

case. It’ll all be sorted later in the code. Somewhat awkward and prone to

errors. Also, battling the compiler like that is a tedious task.

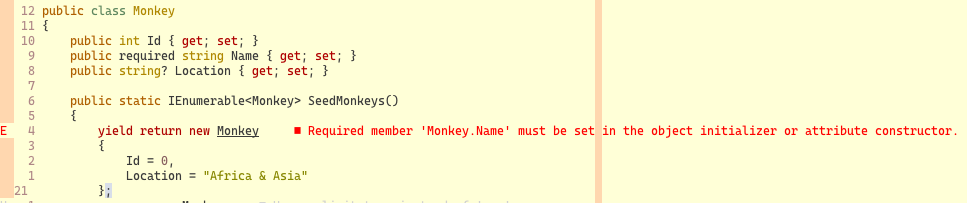

Enter the required keyword. When you flag a property with required, the

IntelliSense engine will report an error if the property value is not set at

initialization, not at declaration.

When someone initializes our class instance, he/she’s required to set an explicit value for our property. Notice how we went from a warning (which will compile) to an error (which won’t compile). Once you start using this feature, it feels so obvious and natural that you wonder why it wasn’t there right from start.

3. C# 11 raw string literals

In C# 11, wrapping a string with triple-double-quotes makes it a raw literal. Its main benefits are that no escaping of double-quotes is necessary, and newlines are allowed within the string.

var xml = """

<element attr="content">

<body>

</body>

</element>

""";

The code looks natural, and no runtime costs for specialized string manipulation are required. One caveat is that string literals naturally remove the indentation when producing the final literal value. The snippet above prints as:

<element attr="content">

<body>

</body>

</element>

We can disable indentation removal like so:

var xml = """

<element attr="content">

<body>

</body>

</element>

""";

String interpolation is also supported:

var json = $$"""

{

"summary": "text",

"length" : {{value.Length}},

};

"""

In hindsight, like the required modifier, raw string literals appear as

obvious.

4. Built-in container support

.NET 7 has built-in container support, meaning that dotnet publish can

now output to a container image instead of a directory. We control image names,

tags, and other settings (like the base image) via dedicated .csproj tags. Two

requirements:

- Docker must be running when we issue the

publishcommand; - The

Microsoft.NET.Build.Containerspackage must be added to the project as a package reference.

In my demo, I had a small console application that I published to a docker image by simply issuing the following command:

$ dotnet publish --os linux --arch x64 /t:PublishContainer -c Release

I did not mention a Dockerfile, and that’s because it is not needed anymore. All my projects deploy to docker containers and are already migrated to .NET 7. I’m currently using Dockerfiles, but I’ll be experimenting with this alternative in the coming weeks, both with builds and remote CI builds.

5. Native AOT

Native AOT produces a standalone executable in the target platform’s file format, with no external dependencies. It’s native, with no IL or JIT involved, and provides fast startup time and a small, self-contained deployment.

In my demo, I just needed to add a <PublishAot>true</PublishAot> tag to the

.csproj, and then the dotnet publish -c Release command produced a

single-file, macOS native executable. You can set the destination platform at

build-time like so:

$ dotnet publish -r win-x64 -c Release

Native AOT will be determinant in a number of use cases, like multi-cloud-deployments, lambda functions, and, in general, hyper-scale services. ASP.NET Core is currently not supported, so we’re limited to console apps.

6 and 7. Rate-limiting and output caching

Ok, these are two, not one. Luckily, my pal Ugo, who was demoing ASP.NET Core 7 parts after me, took charge of showing these.

I briefly mentioned that rate-limiting and output caching are key features in mature production systems. Until today, we had to bake them in-house or rely on third-party packages. I’ve been using LazyCache and AspNetCoreRateLimit myself. The latter recently acknowledged the arrival of rate-limiting in .NET 7 and embraced it in a new package that offers Redis as a rate-limiting backend. Rate-limiting and output caching are now part of the ASP.NET Core framework, and that’s where they belong.

8. Minimal APIs group routes

I know I said 7. I don’t use minimal APIs in production yet, but group routing is beautiful and something I’ll be employing on the first occasion. During the meetup, an interesting (and much-expected) discussion ensued on the usefulness of minimal APIs. Veterans of many battles don’t deem them necessary, especially in real-world use cases, which is actually accurate: one can keep relying on the canonical MVC approach. The sentiment was that Minimal APIs are mostly targeted to newcomers, which is probably true2. As someone coming from the Python REST ecosystem, I dig them a lot. They evolve rapidly and I’m sure we’ll soon see them in action in complex, real scenarios.

To Caesar what is Caesar’s, short on time, I recycled both the idea and the materials from James Montemagno’s excellent video on the same the topic. ↩︎

Back when Minimal APIs were about to debut, I wrote Will .NET 6 Minimal APIs turn heads?, with some musings on their effectiveness and target audience. ↩︎