I came back to reading Shirley Jackson almost by coincidence. I had just finished watching The Haunting of Hill House, and, as I always do with stuff that tickles my curiosity, I was doing a little research on it. That’s how I learned that the TV Series is loosely based on a novel by the same name written by… Shirley Jackson.

Still imbued by the TV Series’s atmospheres, now knowing about its connection with Jackson, I was ready for another dive into her literature of psychological suspense and terror. Terror, not horror. Because one thing to appreciate in Jackson’s writing is that she relies on the former rather than the latter. To elicit emotion in the reader, she uses the tension between characters’ psyches and the complex relationships between mysterious events. Stephen King opens his own novel, Firestarter, with this dedication: “In memory of Shirley Jackson, who never needed to raise her voice.”

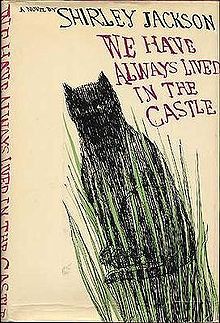

We Have Always Lived in the Castle is a masterpiece. Let’s just marvel for a moment at the mastery of the incipit:

My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all, I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom. Everyone else in my family is dead.

Tone and pace are subtly, masterfully set right there in the opening paragraph.

The main character is already outlined. In hindsight, by the end of the book,

we can tell that we were hinted at a lot more than we initially thought. As

I was reading, I could not help but think how clear and terse Jackson’s prose

is. Only apparently simple, it draws scenes and characters with gem-cut

precision. The unsaid does matter.

Tone and pace are subtly, masterfully set right there in the opening paragraph.

The main character is already outlined. In hindsight, by the end of the book,

we can tell that we were hinted at a lot more than we initially thought. As

I was reading, I could not help but think how clear and terse Jackson’s prose

is. Only apparently simple, it draws scenes and characters with gem-cut

precision. The unsaid does matter.

As Jonathan Lethem once noted, all of Jackson’s work creates an atmosphere of strangeness and contact with a vast intimacy with everyday evil… and how that intimacy affects a village, a family, a self. This is, in fact, true for all the three Jacksons’ works I read. Another common theme is the persecution of people who exhibit “otherness” or become outsiders in small communities, like those found in remote villages. This mirrors the author’s own experience. When she moved with her husband from New York to a small, rural Vermont village, they were isolated and ostracized by the local community. According to Letham, mainly because of anti-Semitism and anti-intellectualism.

In We Have Always Lived in the Castle, however, there is room for love and devotion. Only, they are probably extreme or distorted in sinister and remarkable ways.

This book is brilliant because it takes the canonical witch/haunted house theme and flips it over, instantly reversing the perspective. The story is told from within the house. Village folks are the bad guys. Those who seem to be motivated by good intentions are only fulfilling their own ego or striving to behave with good manners, as society expects them to do. We cannot help but feel at least a drop of compassion and sympathy for the devil.