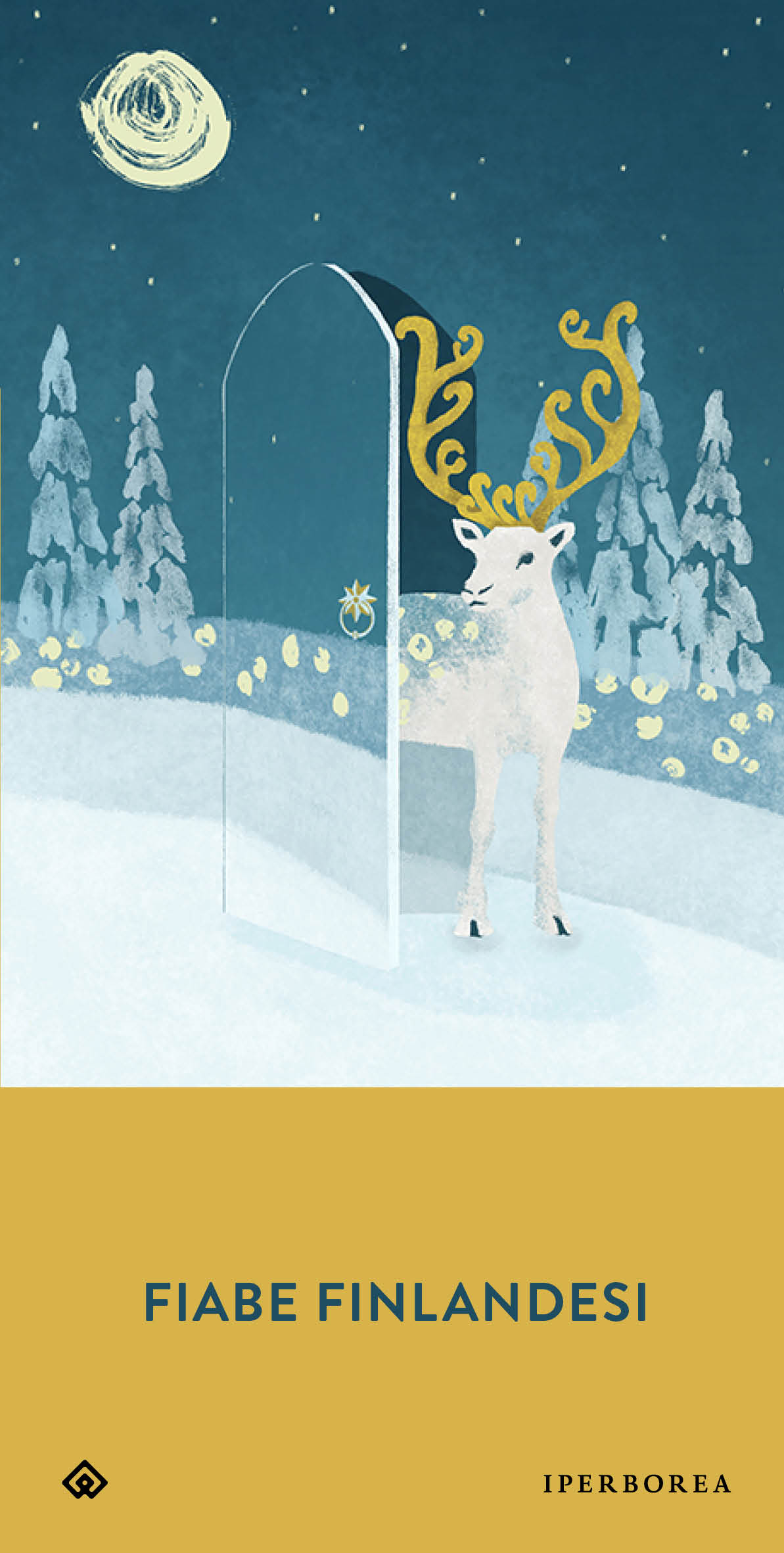

Over the years, Iperborea, one of my favorite Italian publishers, has been publishing an unofficial Nordic Tales series. Their renowned nordic fiction series includes one fairy tale volume per year, usually published in December, just for Christmas. The first book was Lapland Tales in 2014, and then they continued with Danish, Icelandic, Swedish, Faroe, Norwegian, Greenlandic and then Finnish in 2021. I’ve been greedily reading each one of them, usually as my last book of the year. This year I was a little bit late, as reported.

Until now, 2020’s Greenlandic Legends has been my favorite, mainly because it’s

partly different from the others, which all share a common Scandinavian

cultural background. In this regard, this year’s Finnish Tales is even more

remarkable. Quoting the short, excellent final essay by the translators Giorgia

Ferrari and Sanna Maria Martin1:

Until now, 2020’s Greenlandic Legends has been my favorite, mainly because it’s

partly different from the others, which all share a common Scandinavian

cultural background. In this regard, this year’s Finnish Tales is even more

remarkable. Quoting the short, excellent final essay by the translators Giorgia

Ferrari and Sanna Maria Martin1:

Within the Nordic panorama, Finland holds a unique position and has a precise identity: entering Finnish culture means coming into contact with the Finno-Ugric world, starting from the language, which has nothing to do with the Scandinavian ones, which are only geographically close. At the same time, Finland is anything but an island separated from its surroundings: its particular position between East and West has made it, if anything, a borderland, a point of intersection between different cultures, enriching it with influences from both directions. And this can only be evident even in popular tales.

Indeed, in these tales, you find echoes of myths and tropes from Scandinavian culture but always intertwined with unique Finnish themes. Notable examples are:

- The tietäjä, whose supernatural power arises from great knowledge.

- The vetehinen, a male (!!!) water spirit of the forest.

- The syöjätär, the devourer, or the “wicked mother.”

- The nimikkopuu, a tree planted on somebody’s birth; tied to their destiny

- The shamanic rituals, often associated with the use of magical words and songs

The principal collector of Finnish folklore was Eero Salmelainen (1830-1867), who published four seminal titles from which all of the stories in Finnish Tales are selected. Of course, Grimm’s influence is evident in Salmelainen’s work. Remarkably though, Salmelainen started his collection forty years later than the Grimms. One reason might be that until then (and up until now, I might add), Finnish folklore has always been hiding in the shadow of Kalevala’s poetic poetry.

Short, informative essays enrich each one of Iperborea’s Nordic Tales volumes. These are essential in framing the content within the correct background, outlining the links between Nordic cultures, and revealing the sources. Take the Kalevala. I have had it in my library since many years ago, but I didn’t correlate it with Finnish folklore until I saw it mentioned in the essay. [rss]: https://nicolaiarocci.com/index.xml [tw]: http://twitter.com/nicolaiarocci [nl]: https://buttondown.email/nicolaiarocci ↩︎