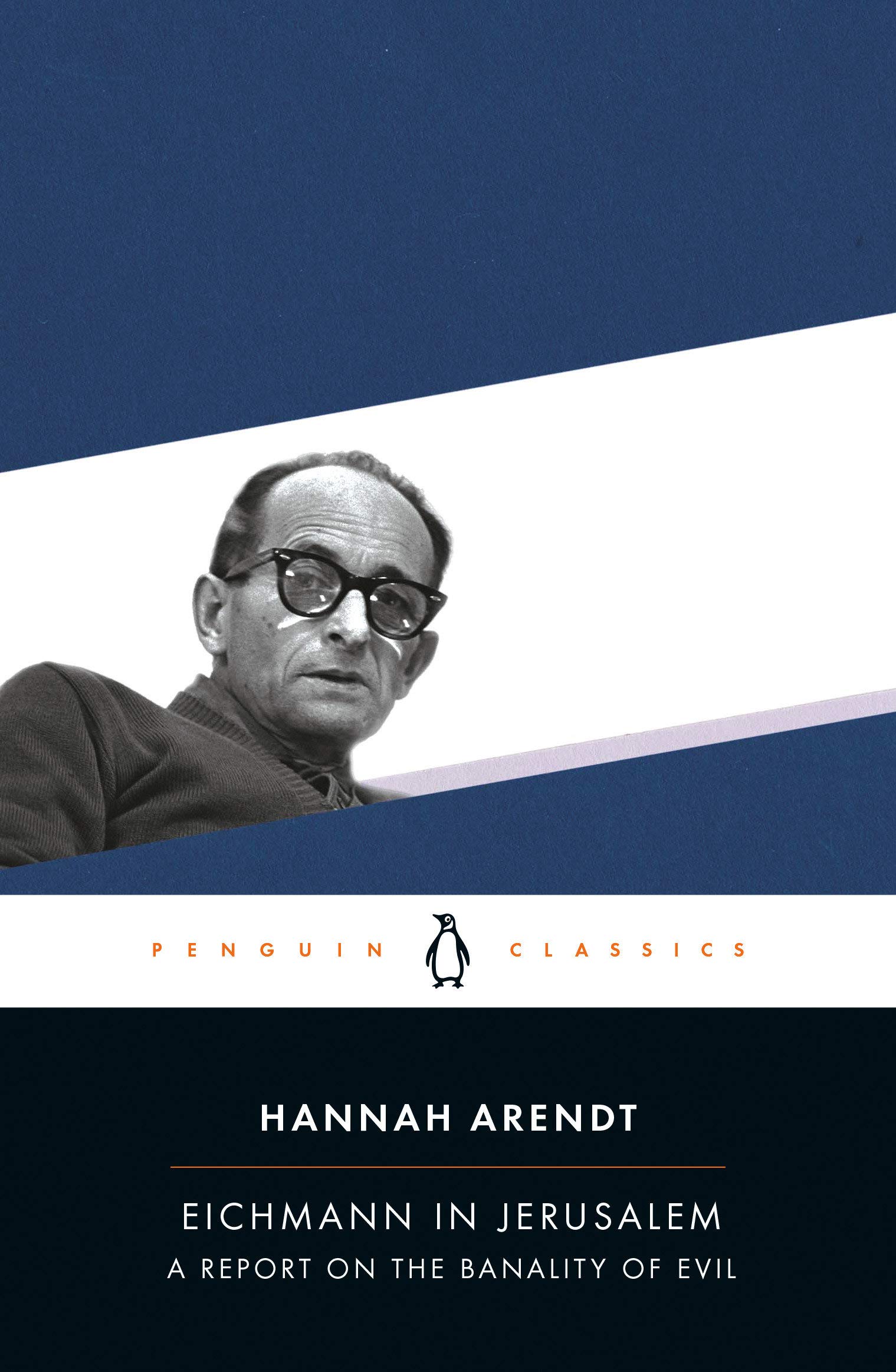

This book is not about the famous, daring, and in some ways fortunate capture of Eichmann in Buenos Aires in 1960, nor about the covert transfer of the Nazi officer to Israel. Instead, the volume recounts the 1961 trial in Jerusalem, which ended with the defendant being sentenced to death. Hannah Arendt followed the trial as a correspondent for The New Yorker. She took notes, studied the papers, and reconstructed the many witnesses’ personal stories. Her work was first published as articles in The New Yorker and later revised and updated as a book.

Following the trial hearings, we are taken back to the years of the advent of

Nazism in Germany. The regime first incited and then actively advocated

anti-Semitism, a historically present sentiment in many parts of Europe and

beyond. These are the years of establishing the SS and other Nazi police

forces. Eichmann, penniless and unemployed, managed to join the SS ranks thanks

to an acquaintance. He was appointed to the Jewish emigration office, an

assignment he took seriously. He read books and became an “expert on the Jewish

question”. Over time, Eichmann career progressed as his office duties evolved,

from emigration to deportation and extermination. However, despite the

undoubted successes, Eichmann never managed to reach the highest levels of the

military hierarchy. He could never get close to his idol, the Führer. For what

reason?

Following the trial hearings, we are taken back to the years of the advent of

Nazism in Germany. The regime first incited and then actively advocated

anti-Semitism, a historically present sentiment in many parts of Europe and

beyond. These are the years of establishing the SS and other Nazi police

forces. Eichmann, penniless and unemployed, managed to join the SS ranks thanks

to an acquaintance. He was appointed to the Jewish emigration office, an

assignment he took seriously. He read books and became an “expert on the Jewish

question”. Over time, Eichmann career progressed as his office duties evolved,

from emigration to deportation and extermination. However, despite the

undoubted successes, Eichmann never managed to reach the highest levels of the

military hierarchy. He could never get close to his idol, the Führer. For what

reason?

Why couldn’t he ever get into Hitler’s inner circle? The critical point of Eichman in Jerusalem is, I think, precisely the answer to this question. According to Arendt’s reconstruction, Eichmann was and always remained a mediocre man. He was undoubtedly a good bureaucrat, an expert in organization and logistics, but light years away from the brilliant and appealing person he always aspired to be. Arendt makes no discount, reporting the many moments during the process in which Eichmann reveals his true stature.

The banality of evil of the title lies precisely in this aspect: a modest bureaucrat who merely fulfils his job slavishly, without questioning his role, as a cog in the machine, can do evil. The Nazi machine exterminated six million Jews, and the office Eichmann directed was the fulcrum of that tireless activity. And yet, the man in charge, and with him, his subordinates, for the most part, were ordinary people who carried out their tasks heads down, no questions asked. How many Germans (and collaborators in the occupied countries) did the same thing in those years?

Since its publication, the book has not ceased to raise controversy, particularly concerning the role of Jewish Councils of Elders (Judenrat), organizational structures imposed by Nazi Germany. Arendt proposes that they actively collaborated in drawing up the lists of Jews to be deported. In any case, Eichmann in Jerusalem is an exceptionally documented and well-argued historical research. It is worth reading, especially so in our time when the memory of time passed tends to fade away.