Daniil Charms was considered a children’s author and could not stand children all his life. While his whimsical fairy tales populated illustrated books and magazines, giving him something to live on in the silence of his room, he also feverishly wrote tales for adults, equally imaginative but inhabited by an excruciating melancholy, as in fairy tales went wrong.

At the dawn of the USSR, this desperate fantasy of his was tolerable only if it was confined where it was least dangerous, in children’s literature. Back then, adults were the children to be motivated and consoled with uplifting novels aimed at glorifying the rise of the proletariat, a literature Charms refused to adhere to.

Thus, while socialist realism raged outside, Daniil Charms uncovered impossible worlds in the folds of reality. Gossipy older women tipping over the window, curious people breaking their watches trying to seize the moment, men buried alive rejoicing at the beautiful funeral, birds equipped with teeth (or maybe not), deadly challenges at cucumber blows, caterpillars with their snouts covered in dust.

This book is an arsenal of incredible stories circling for a long time, only clandestinely in samizdats, illegal books recopied by hand or typed in secret. Credit goes to Paolo Nori, who revealed to the Italian readers the greatness of this pioneer of the literature of the absurd. Nori selects and assembles hundreds of narrative fragments, alternating with excerpts from the diaries, in which Charms lays bare his tragic everyday life. The fresco of tightrope walking characters and unbelievable animals is thus interwoven with the minute account of a sour life lived on the fringes of literary society until the gloomy eye of the Party rests on this wacky dissident.

The Soviet Union tried multiple times to erase Charms by letting him die in an asylum. They finally succeeded on February 2, 1942, when famine killed him in the psychiatric clinic in which he was confined.

Most of these things were written when socialist realism triumphed around, and their author knew very well that he could never publish them in his lifetime. Yet, by reading his diaries, all this “nonsense,” as Charmes defined his crazy writing assembly, clearly emerges as the most crucial thing in his life.

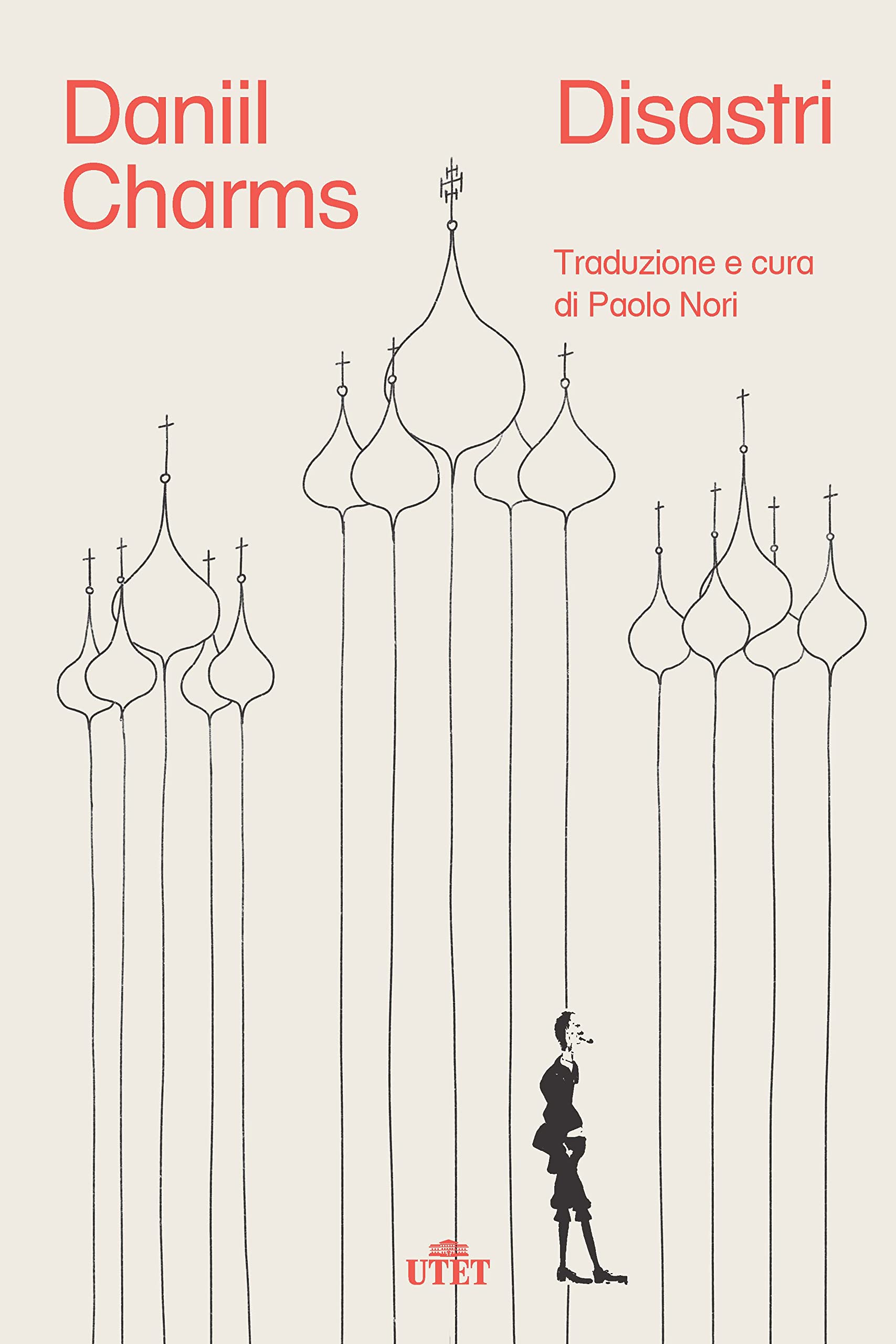

I found the book cover excellent and perfectly fit, with this dandy figure seemingly strolling amongst imposing orthodox buildings. According to Wikipedia, Charms loved to appear dressed like an English dandy and with a calabash pipe.